Geographic and Systemic Obstacles

The tour demonstrated that poverty has no geographic bounds. From crowded urban centers with available resources and programs to rural communities with far fewer people and less readily-available services, the dimensions of poverty came into focus despite these regional differences. While geography presented challenges, disadvantaged people living in cities and rural areas faced remarkably similar issues. Men, women and children across the state delineated a general set of issues and barriers.

Populations in cities and rural regions faced hunger, difficulty in obtaining housing, lack of quality jobs, drug abuse, domestic violence and discrimination of a social, cultural and racial nature, among other factors. Likewise, and regardless of geographic boundaries, individuals faced high barriers in accessing transportation, mental health services, housing and social services.

Across the state, individual stories provided a detailed portrait of the ways men and women cope with economic difficulties. Despite the similarities in their settings and circumstances, impoverished men and women in urban and rural areas had different methods of dealing with such conditions.

Rural poverty comes with logistical obstacles to a living wage, including transportation and access to education and services. Simply put, needed resources may be many miles away with few options to retrieve benefits.

Leesa and her children would walk one and one-half hours home at the end of each workday. As a person without resources, Leesa said that it was difficult to find a job if one is not available within a walkable distance. She said this was an extreme impediment to employment.

There have been many academic reports portraying the impact of poverty on rural regions. One report from PBS focused on the divide between urban and rural indigence (Thiede, Greiman, Weiler, Conroy, & Deller, 2017). It noted that a large swath of the rural workforce lives just above the poverty line and in economically-exposed circumstances (Thiede, Greiman, Weiler, Conroy, & Deller, 2017). Almost 20 percent of rural households were in families with incomes less than 150 percent of the poverty line (Thiede, Greiman, Weiler, Conroy, & Deller, 2017).

Rural communities across the nation have failed to recover the jobs lost in the recession.

In the region where Dave resides and works, the area was devastated by economic globalization.

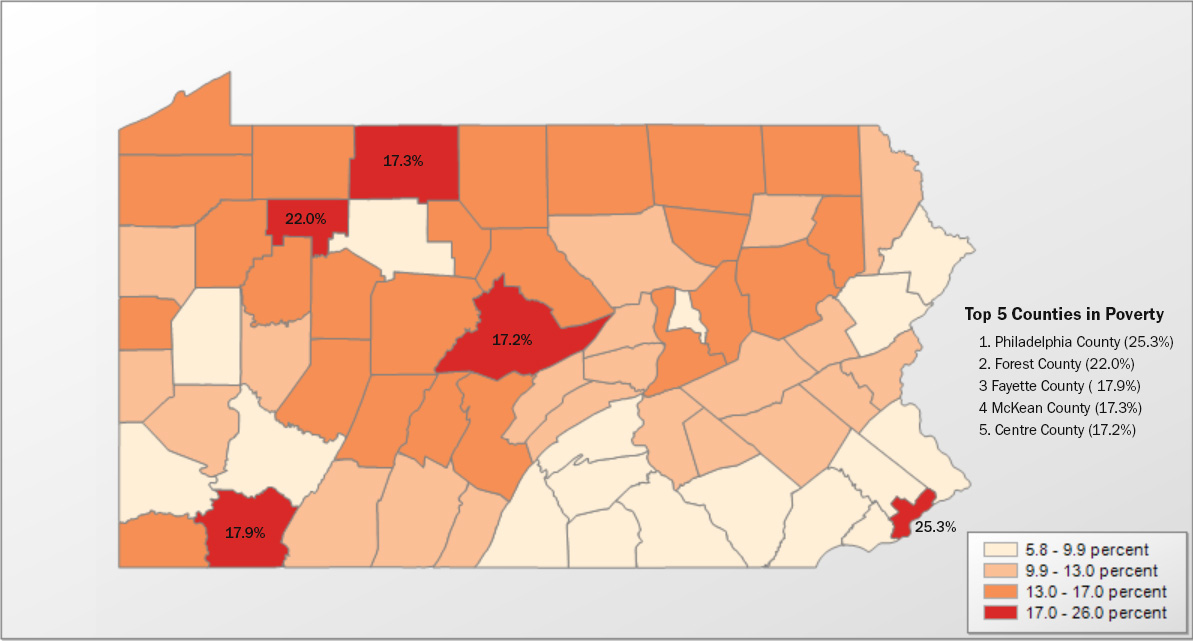

As it relates to Pennsylvania, the geography of poverty can be examined using a map of statistics gathered from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019).

The map paints a striking picture of ways poverty has infiltrated urban and rural regions. The common viewpoint of poverty as an issue nearly exclusive to urban areas is erroneous (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019). Simply put, there are several counties across the state where poverty is a strong characteristic of the population.

As compared on a per capita basis, while more than 25 percent of the population is impoverished in Philadelphia, in excess of 22 percent of the population of Forest County in northcentral Pennsylvania also lives in poverty (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019). The rural Fayette and McKean Counties also have high poverty rates – over 17 percent (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019). Centre County, home of Penn State University and the location of several state-of-the-art technology companies, has a poverty rate of 17.2 percent (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019).

Percent of total population in poverty, 2017: Pennsylvania

Personal accounts of individuals from urban and rural settings dealing with the challenges of poverty are instructive.

In urban areas, social services are more readily available, but, as testimony demonstrated, there are complications in accessing assistance. From distrust and outright hostility toward the programs to a lack of help from county assistance workers and security challenges, individuals living in poverty in large cities and populous communities experienced frustration.

Cherri expressed frustration with the county assistance offices. She said she always hands her paperwork directly to someone at the office, but, regardless of these efforts, her paperwork fails to be processed. She received a letter from Social Security explaining she was going to lose disability benefits because the office had not received her paperwork.

Dominique said county assistance workers do not fully understand programs and have been unable to convey details about how programs can help.

Beyond geographic issues, several people focused on what many viewed as organizational or physical barriers to advancing themselves toward self-sufficiency. Frustration with the barriers manifested itself in several ways.

There were consistent comments related to barriers that prevented greater progress out of poverty. Whether in rural areas or in urban settings, men and women repeatedly cited transportation, housing, food, education and poverty wage jobs as obstacles in their path to self-sufficiency.

The obstacles that were noted created gaps in the ability of programs to reach those in need. Regardless of the depth of their poverty, better public transportation, availability of safe, secure and affordable housing, enhanced education and job prospects and access to more and higher quality food were issues that led to insecurity and hardship. When the logistics related to these issues were out of place, the individuals reverted to clinging to sustenance and forgoing attempts to move out of poverty situations.

One of the largest challenges cited by those experiencing poverty was the lack of accessibility to quality job opportunities and living wages. The lack of family-sustaining job opportunities and meaningful education and job training were key elements in many Tour presentations.

A near universal impression among those who testified suggested that access to education and skill development was a pathway out of poverty. Many realized that the lack of education restricted their economic mobility.

To address low wages, Rochelle said more employment skill training is needed and skill- enhancement would help produce living wages.

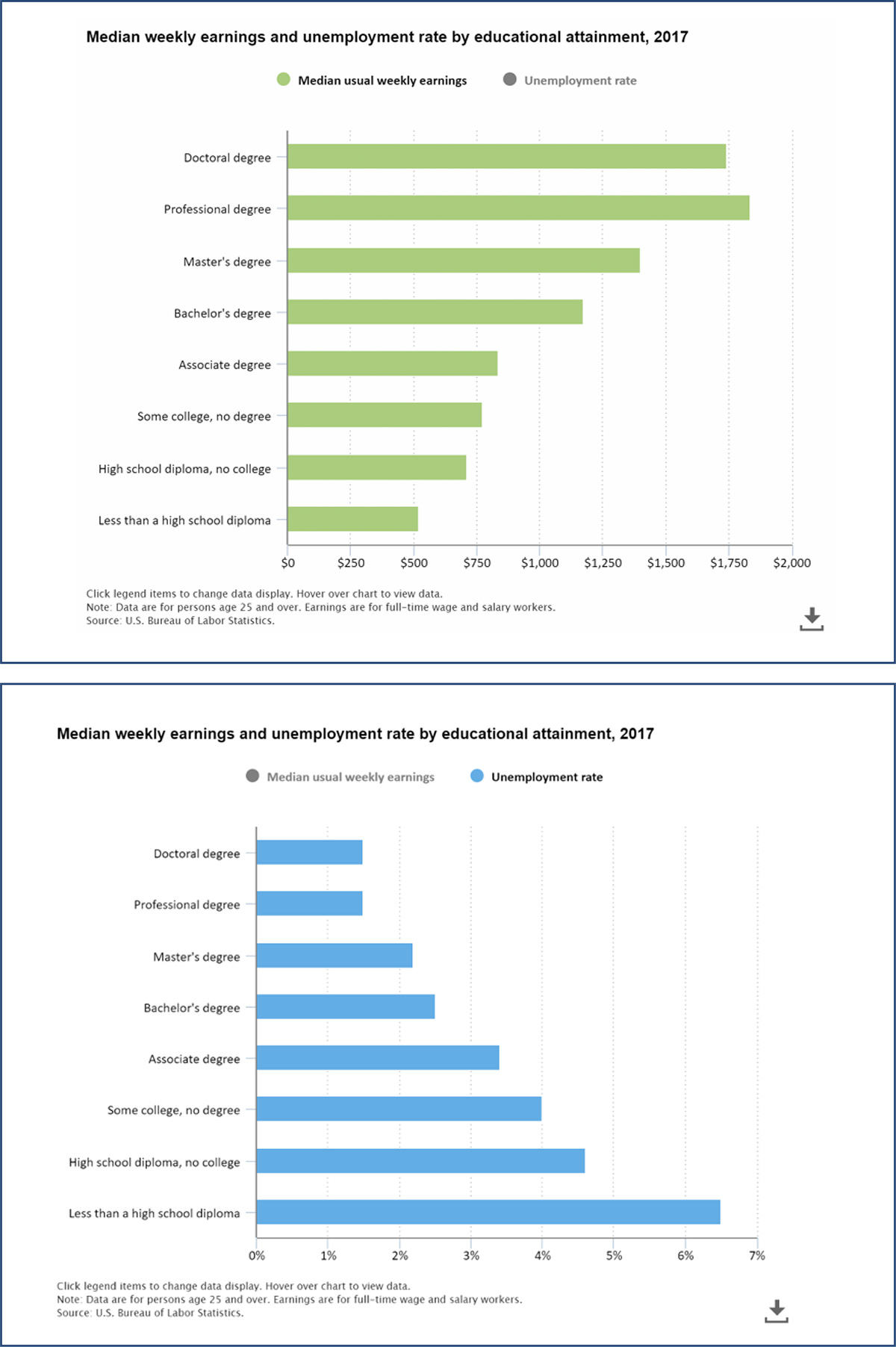

According to a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report, “Poverty in the United States: 50-Year Trends and Safety Net Impacts,” which examined poverty over a 50-year period, education is a key determinant of poverty (Chaudry, et al., 2016).

The poverty rate of those who did not graduate high school is two or three times higher than that of high school graduates (Chaudry, et al., 2016). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services also reports that the poverty rate for people with only a high school diploma has nearly tripled over the 50-year period (Chaudry, et al., 2016). The report noted that poverty rose significantly during times of economic distress (Chaudry, et al., 2016).

Examining the two charts from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, reveals that people who are 25 and older with less education have lower weekly earnings and higher unemployment rates than those with an advanced education.

The good news for some who testified was that after experiencing years of impoverishment, they sought out educational programs to advance academically and build their skills in selected fields. Often, these efforts were successful and contributed to greater income and stability.

EMPLOYMENT PROGRAMS

for people who receive public benefits in PA

The Pennsylvania Department of Human Services has programs that help those receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and/or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits prepare for, find, and keep employment. While some are required to look for work in order to keep their benefits, many others voluntarily enroll in the programs. Here is what is available:

WORK READY

WHAT IS IT? Program that provides case management to help people prepare for and secure employment.

WHO DOES IT SERVE? People who receive TANF and/or SNAP benefits.

GOALS: Active participation in the program that leads to enrollment in EARN, KEYS, or employment.

KEYS

WHAT IS IT? Collaboration with community colleges to assist people who receive benefits with completing certificates, degrees, and credentials.

WHO DOES IT SERVE? People who receive TANF and/or SNAP.

GOALS: Course completion, graduation, and employment.

EARN

WHAT IS IT? Program assisting people with transition from receiving public benefits to being active members of the workforce.

WHO DOES IT SERVE? People who receive TANF benefits.

GOALS: Job placement and retention, credentialing, no longer needing TANF.

SNAP 50/50

WHO DOES IT SERVE? People who receive SNAP benefits.

GOALS: Program completion, job placement, and job retention.

Source: Pennsylvania Department of Human Services

http://www.dhs.pa.gov/publications/infographics/employmentservices/

Leesa is working through a medical assistant certification program paid for in part by Trehab. She hopes to find a job as a receptionist and medical biller at a doctor’s office. She said medical billers make $12 to $15 per hour.

Far too many people seek education and training but are restricted by a lack of access. The provider panel noted that those seeking high school diplomas through GED programs were often rebuffed due to lack of space in classes. There is a far greater demand for such courses than there are slots available.

The provider panel also noted that earlier access to education improves outcomes. They claim that support early can help stave off poverty later. Those who receive a high school equivalency said the learning process cannot end with a GED.

Toni focused a great deal on education in discussing her plight. She said that more educational opportunities and information about programs are needed to aid those struggling with poverty.

Testimony was also offered about the frustrations with seeking greater skills and education but being stuck in low-wage professions with limited advancement opportunities. Many of these individuals had limited means but were then hobbled by high student loan repayment bills.

Jasmine described her efforts as she tried to navigate her way through a variety of challenges. She was trained and worked as a medical assistant. Despite her training and employment, the work resulted in low wages with no benefits. Her wages were frozen, and she needed food stamps to help cover expenses. She also carries more than $15,000 in student loan debt.

Transportation was high on the list of obstacles. Access to effective, efficient and inexpensive transportation was on the minds of many. It was clear the inability to get to work, school, child care or medical appointments created a barrier to advancing from poverty. The often-mentioned way to address inadequate public transit – walking to destinations – was not possible in many situations. The result was the loss of access to job opportunities or job training.

The inability to find suitable and convenient transportation to get to a job or work-training session compounded an already-difficult job search, given their lack of skills, many said. Transportation barriers limit those searching for work to near their homes and effectively limit the range of their job searches, essentially tying down those who sought change.

Far too many of the persons who testified settled for insufficient alternatives because they were dealing with other complications of their respective situations.

Living without a car, Tyran walks to destinations due to the complexity of syncing his schedule with that of the bus system.

A recent paper underscores the importance of effective transportation in addressing poverty. A report in the Chicago Policy Review, “How Public Bus Routes Can Deconcentrate Poverty and Promote Equity” (Miller, 2018), concluded that “more robust public transit options can help deconcentrate poverty and promote equity and inclusivity across different areas” (Miller, 2018). This report was based on an analysis of census tract data over an extended period (1970 to 2010) looking for a correlation between access to transportation and poverty (Miller, 2018).

In urban areas, public transportation was generally available (Miller, 2018). Scheduling and service availability to work in symmetry with public transportation presented difficulties (Miller, 2018). This was especially difficult in many service jobs that required working through the night, weekends and holidays (Miller, 2018).

Shore mentioned transportation as a significant hurdle for those struggling with poverty. Regarding transportation, multiple issues were raised. Rate increases, changes to the ConnectCard system, inconvenient scheduling and unavailability of service hampered upward economic mobility.

In Erie, several testifiers said they believed they could acquire enhanced job training, which would provide better jobs and lead to self-sufficiency, but public transportation access was sketchy. If they used the bus to get to a potential job training site, the service was either two hours early or two hours late, making public transportation functionally unavailable.

They added that the alternative to public transportation was an ad hoc system that neither promised, nor guaranteed, reliability. The shortage of options impacted a wide range of life-decisions, often with less-than-desirable results.

To deal with the lack of transportation access, some men and women relied on family members or friends for transportation. Depending on family and friends to fill in for public transit was necessary, but a burden, they testified.

In rural areas, transportation was identified as a significant hurdle. If public transportation was available at all, it was infrequent. Visits to job sites, skills training, medical care and access to other services was so difficult that it was almost unachievable.

Again, those persons living in rural areas had to rely on family and friends. According to testimony, officials in rural areas know of the inherent problems developing a schedule to help residents. Often, they are constrained by costs and efficiency demands.

Transportation issues remain a major challenge for the poor in rural areas, Dave said.

Another often mentioned barrier is related to housing. The availability of suitable housing that is both secure and affordable was cited as a great and often harrowing problem. Some individuals testified they were forced to live in substandard housing with landlords who did not care to fix broken pipes, walls, leaks and other problems – or were loath to put any effort or money toward repairs. Others said that because affordable housing simply was not available, it forced them to seek housing in shelters or become homeless.

Ike echoed the comments of many others in expressing frustration with the lack of available quality housing options. He has been to several senior citizen housing venues where he has “been given the run-around,” experiencing long wait times on the phone or never receiving a call back. He has applied for new senior citizen housing for the past five years. He has been living with his daughter for eleven years.

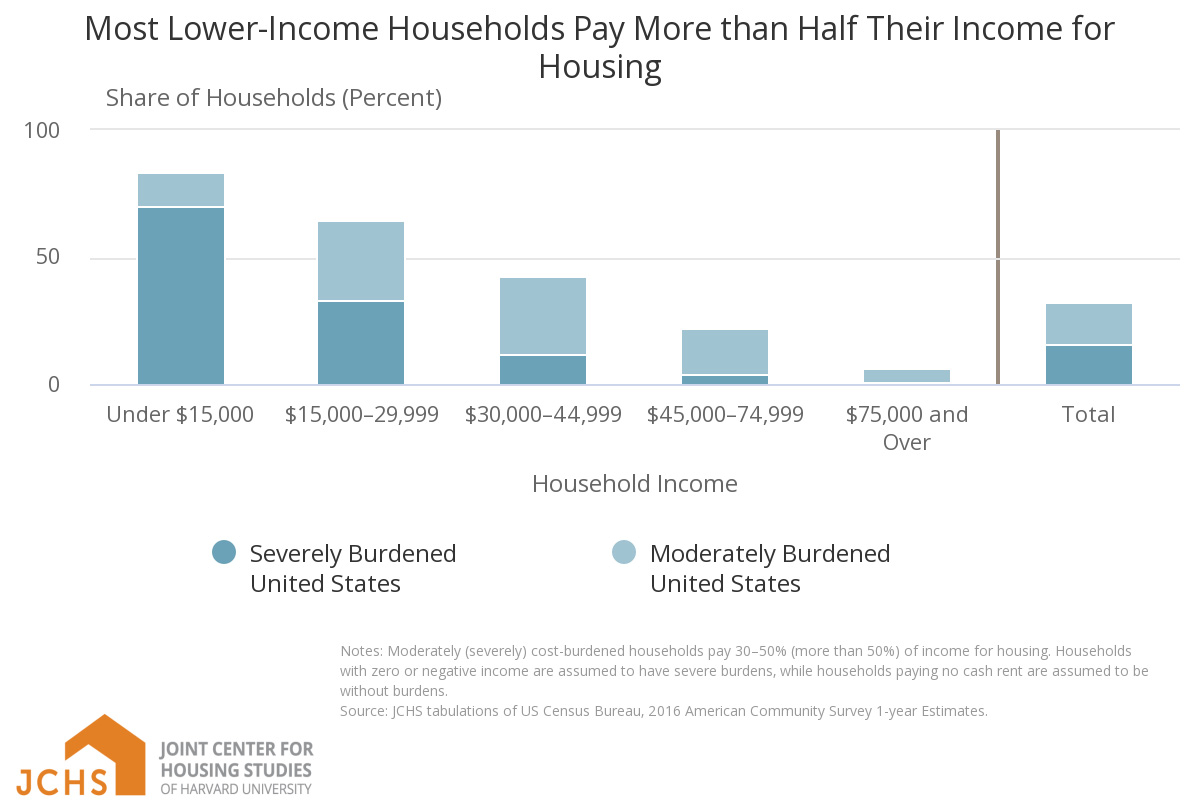

Harvard University looked at the state of housing in the United States in 2018, reporting that over 70 percent of households with incomes below $15,000 paid more than half of their income for housing (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2018).

Source: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2018.

Equally troubling and related to housing availability were the safety and security concerns expressed by individuals persisting in exceptionally tough situations. Fear for personal safety, and security concerns for members of the family, prompted some people to flee from housing in search of refuge in the homes of family members, public shelters or the streets.

Helen has been dealing with housing insecurity for 18 years, since a fire destroyed her home in 2001. For the next 7 years, she spent time in and out of shelters, or floating between friends’ and family’s homes, until she had to return to the shelter regularly in 2008.

Hunger was a notable barrier mentioned prominently in tour discussions. According to the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, food insecurity is the “disruption of food intake or eating patterns because of lack of money and other resources” (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). Food availability, nutrition and reliable access is a threat (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). Many testifiers who were enrolled in and received SNAP benefits lamented the limitations. They noted the amount of SNAP benefits had to be stretched each month to cover their food needs.

Concerns of individual participants ranged from limited stipends and budgeting for groceries to the quality of nutrition and related health risks resulting from unbalanced diets. Concerns were also expressed for certain populations who could not access enough food, notably college students.

Relative to SNAP benefits, Linda said she receives $114 per month or $28 per week, which makes it exceptionally difficult to get enough healthy foods.

Dominique said SNAP benefits are not enough and that trying to live on food stamps is exceptionally difficult. The amount of food stamps available – $112 per month – also leads to unhealthy eating habits.

According to Feeding America, nearly 60 percent of food-insecure households used at least one federal food assistance program (Feeding America, n.d.). These programs include SNAP, school lunch program and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) (Feeding America, n.d.).

During the tour, alternative strategies were discussed for accessing meals outside of the federal food stamp program. These include attending meals hosted by faith-based groups and non-profits. Also mentioned were ideas for stretching SNAP benefits to cover the month.

Another barrier issue discussed over the course of the testimony was addressing child care needs. It was argued that affordable child care prevented individuals from seeking additional job training, better jobs and greater opportunities. Affordable, quality, safe and secure child care access was a significant challenge.

Ntambese identified child care as an issue that makes dealing with poverty more difficult. She expressed a great deal of worry over the loss of benefits when program income guidelines are exceeded.

Child care responsibilities required many individuals to limit their job searches, educational pursuits and careers.

Leesa cited lack of flexible child care as another high barrier to finding employment. Leesa said evening and weekend child care is needed but is generally unavailable, leaving folks with limited job experience fewer employment opportunities outside regular working hours.

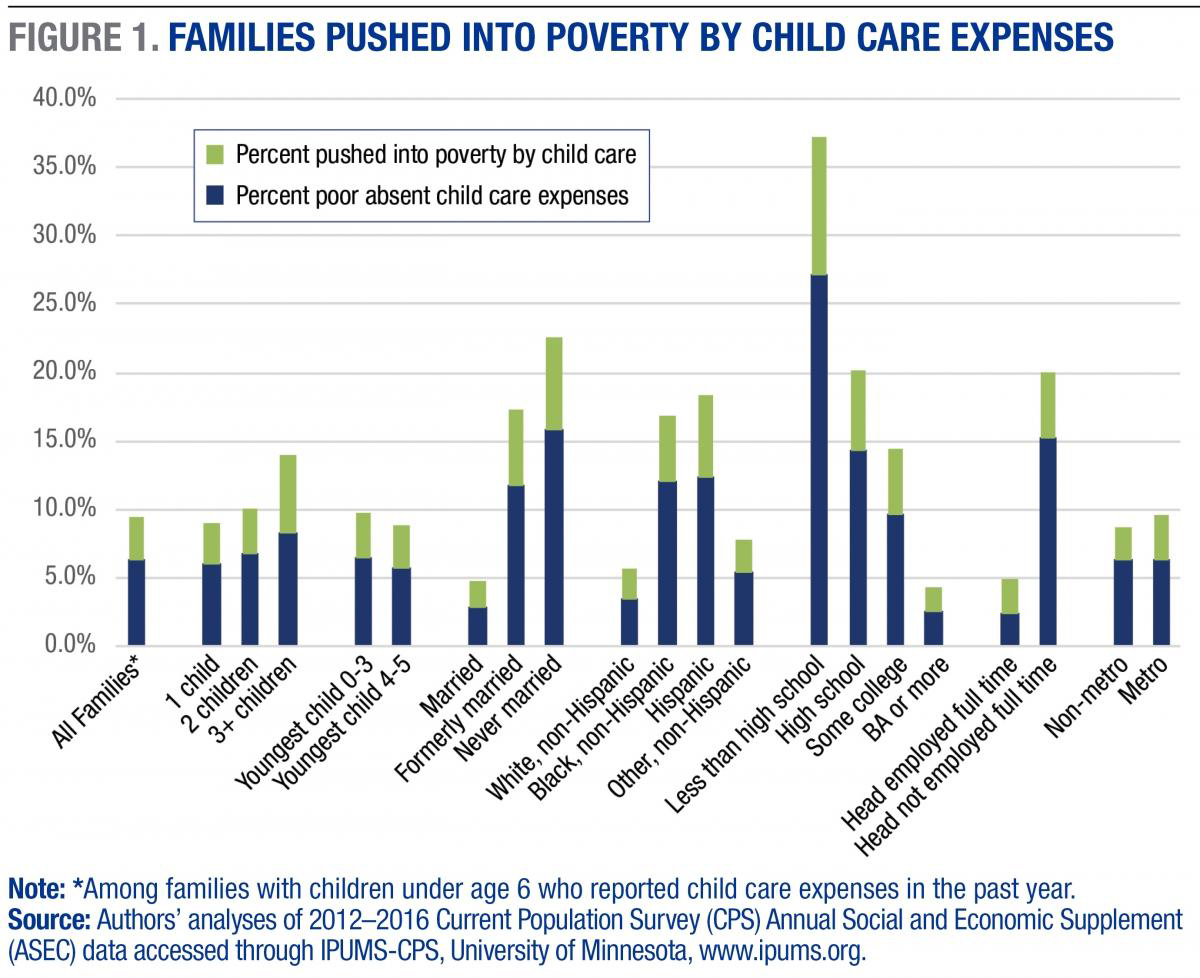

According to a report from the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire, nearly a third of families with young children are poor (Mattingly & Wimer, 2017). Among families paying for child care, almost one in 10 are poor, and a third of these families are “pushed into poverty by child care expenses” (Mattingly & Wimer, 2017). The study found that an estimated 207,000 families were pressed into poverty as a result of child care costs (Mattingly & Wimer, 2017).

Source: Mattingly & Wimer, 2017.